- Recruitment and retention

- External comparability

- Bargaining Agent proposals

- Employer proposals

- Damages related to the Phoenix pay system

The Government of Canada is committed to good faith negotiations and has a history of negotiations that are productive and respectful of its dedicated workforce. Its approach to collective bargaining is to negotiate agreements that are reasonable for public service employees, bargaining agents, and the Canadian taxpayers.

Through good faith bargaining, the Government of Canada has reached 34 agreements during the current round of negotiations, covering more than 65,000 employees in the federal public service. This includes 17 agreements with 11 bargaining agents representing employees working in the CPA, as well as 17 agreements with four (4) bargaining agents representing employees working in separate agencies, including the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), the National Research Council (NRC) and the National Film Board (NFB).

All 34 agreements cover a four-year period, and include pattern economic increases of 2.0%, 2.0%, 1.5% and 1.5%.

The settlements also include targeted improvements valued at approximately 1% over the term of the agreements. For most of the 34 groups, these improvements take the form of wage adjustments staggered over two years: 0.8% in year one and 0.2% in year two. This includes the Economics and Social Services (EC) group represented by the Canadian Association of Professional Employees (CAPE), the Financial Management (FI) group represented by the Association of Canadian Financial Officers (ACFO), and the Architecture, Engineering and land Survey (NR) groups represented by the Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada (PIPSC). For some other groups, including the Audit, Commerce and Purchasing (AV), the Health Services (SH) groups represented by PIPSC, and the Foreign Service (FS) group represented by the Professional Association of Foreign Service Officers (PAFSO), the parties jointly agreed to distribute the 1% differently based on the specific circumstances of each group; however, the total value of those targeted adjustments does not exceed 1%.

For all the agreements settled to date, the overall average annual increase is 2.0% per year over four years, before calculating the compounding effect. This takes into account the pattern economic increases of 2%, 2%, 1.5% and 1.5%, and the targeted increases valued at 1% over the term of the agreements.

Moreover, the settlements include a number of government-wide improvements that increase the overall value of the changes to the collective agreements. These include the introduction of new leave provisions for domestic violence and caregiving, improvements to the maternity and parental leave and allowance provisions, as well as an expansion to the definition of family that broadens the scope of certain leave provisions.

In addition, all the 34 agreements include the identical Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on the implementation of collective agreements. The MOU outlines the new methodology for calculating retroactive payments and provides for longer timelines for implementing the agreements. The MOU also includes accountability measures and reasonable compensation for employees in recognition of the extended timelines.

Given the pay and HR systems in place and the ongoing challenges with pay administration, the Government of Canada has no flexibility to implement agreements on a different basis than what is included in the negotiated MOU. Agreeing to a different implementation process and timelines would represent bad faith bargaining on behalf of the government, as it would be agreeing to something that it cannot fulfill.

The evidence and analysis included in this presentation, which include information on recruitment and retention, external comparability, and the total compensation package provided to employees in the SV group, does not support providing economic increases and other non-monetary improvements to the SV group that deviate from the established pattern with the 34 groups in the federal public service. The information demonstrates that these employees benefit from competitive terms and conditions of employment and that the Employer’s offer is reasonable and fair in the current economic environment.

Recruitment and retention

Section 175 of the Federal Public Service Labour Relations Act (FPSLRA) (Exhibit #2) states that a public interest commission must take into account recruitment and retention considerations in the conduct of its proceedings and in making its report:

a) the necessity of attracting competent persons to, and retaining them in, the public service in order to meet the needs of Canadians;

The evidence on recruitment and retention strongly suggests that compensation levels for the SV group are appropriate to attract and retain a sufficient number of employees. There is no indication that increases above the pattern established to date for the federal public service with represented employees are needed to recruit and retain employees in the SV group.

The hiring departments of SV employees, which include Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Correctional Service Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, National Defence, Public Services and Procurement Canada and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (Civilian Staff), have not identified widespread recruitment and retention issues for the SV group. External separations, especially as they pertain to voluntary separations for reasons other than retirement, are very low – only 0.7% of employees in the SV bargaining unit. In addition, departments run successful recruitment processes for the SV group.

The Public Service Employee Survey (PSES) results indicate a very high level of job satisfaction in the SV group as a whole, with approximately 88% of employees in the group reporting to liking their job. This further supports the notion that the SV group is healthy from a recruitment and retention standpoint.

External comparability

Section 175 of the FPSLRA also states that a public interest commission must take into account external comparability in the conduct of its proceedings and in making its report:

b) the necessity of offering compensation and other terms and conditions of employment in the public service that are comparable to those of employees in similar occupations in the private and public sectors, including any geographic, industrial or other variations that the public interest commission considers relevant;

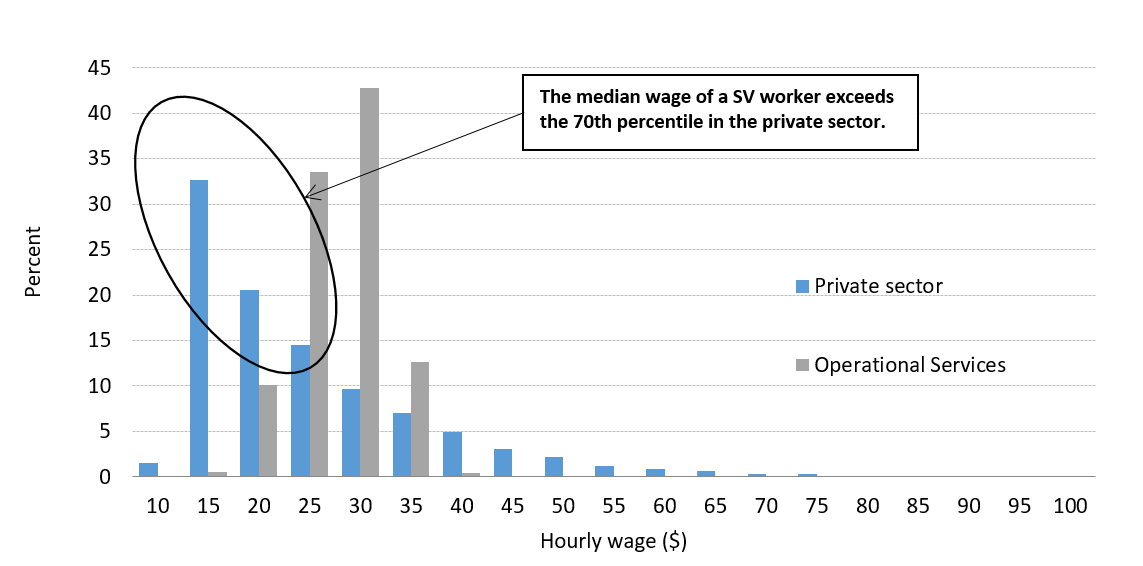

As noted in the 2019 pay study conducted by Mercer Canada LLC, an independent HR firm with significant expertise in conducing wage comparability studies, evaluated the 2017 salaries paid to employees in 18 benchmark positions in the SV group. The results of the study show that SV wages are either competitive with or leading with the 2018 salaries paid in the external the market for comparable jobs for all but one position.

Moreover, the wage growth for the majority of the SV subgroups (40.5% to 93.9%) has significantly outpaced cumulative increases as represented by the change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation (36.8%) between 2000 and 2017.

It should also be noted that Mercer performed a joint wage study with the PSAC to determine market relativity for the Ships’ Crews (SC) group positions within the SV Group. Primary research was completed based on the benchmark roles for the SC group. The results showed that the SC group currently have wages that are comparable with the market.

Bargaining Agent proposals

The Bargaining Agent has submitted an extensive list of proposals in this round of bargaining.

The PSAC has tabled 19 proposals that are common to all PSAC groups, including above pattern economic increases, two additional designated paid holidays per year, and increased vacation leave entitlements.

The PSAC has also tabled 55 changes that are specific to the SV table, within 22 articles and 6 appendices. These changes include increases to leave provisions, new allowances, and other monetary and non-monetary elements that currently do not exist in the SV agreement and/or in other collective agreements in the CPA.

As noted in the table below and detailed in Part II, Table 4, the PSAC monetary proposals are significant and represent a total ongoing cost of over $268 million or 37.87% of the SV group wage base. Footnote 1

| Bargaining Agent monetary proposals | Ongoing cost | % of wage base |

|---|---|---|

| Common proposals | $9,771,593 | 1.38% |

| SV-specific proposals | ||

| Economic increase of 3.25% over three years | $73,114,585 | 10.33% |

| Wage adjustments | $84,470,416 | 11.93% |

| Wage restructures | $14,645,436 | 2.07% |

| Other monetary improvements | $86,103,481 | 12.16% |

| Total | $268,105,510 | 37.87% |

The Employer’s position is that the Bargaining Agent’s proposals violate the replication principle, where the results of a third-party process should replicate as closely as possible what would have been achieved had the parties negotiated a settlement on their own. The Employer submits that the Bargaining Agent’s proposals do not reflect what the parties would have bargained.

Additionally, the PSAC’s proposals are unsubstantiated based on available data and associated metrics related to recruitment and retention and internal and external comparability.

Employer proposals

The Employer is of the view that the SV agreement is a mature agreement that does not require major changes. As such, the Employer is submitting a reduced package of proposals that includes modest economic increases and changes to leave provisions that are aligned with what has been agreed to with 34 other groups in the current round of bargaining.

The Employer’s monetary proposals, with the associated costs, are included below.

| Employer monetary proposals | Ongoing cost | % of wage base |

|---|---|---|

| Common proposals | ||

| 10 days of paid leave for domestic violence | $94,671 | 0.01% |

| Expanded provisions for definition of family (various articles) | $411,612 | 0.06% |

| Parental leave without pay (standard/extended period) | Cost neutral | 0.00% |

| Caregiving leave without pay related to critical illness | $520,278 | 0.07% |

| SV-specific proposals | ||

| Pattern economic increases over four years: 2.0%, 2.0%, 1.5%, and 1.5% | $50,880,482 | 7.18% |

| An additional 1% for group-specific adjustments | $7,496,919 | 1.06% |

| Total | $59,403,962 | 8.39% |

The Employer’s proposal also includes the MOU on the implementation of the collective agreement negotiated with the 34 other groups in the federal public service (Exhibit #3). Given the pay and HR systems in place and the associated challenges, the Government of Canada has no flexibility to implement agreements on a different basis. Agreeing to a different implementation process and timelines would represent bad faith bargaining on behalf of the government, as it would be agreeing to something that it cannot fulfill.

Given the high volume of outstanding proposals submitted by the Bargaining Agent, the Employer requests that the PSAC target a limited number of proposals that take into account the current collective bargaining landscape and recent negotiation outcomes with other federal public service bargaining agents. The large number of proposals make it challenging for the parties to identify and focus their work on key priorities; a more limited number of proposals is expected to meaningfully improve the likelihood of settlement. The Employer respectfully suggests that the Commission issue a direction in that regard and direct the parties to return to negotiations with a reduced number of proposals, prior to the issuance of the Commission’s report.

Damages related to the Phoenix pay system

In 2017, the PSAC and other CPA Bargaining Agents chose to create and mandate a joint senior-level Employer-Union Phoenix subcommittee to resolve the issue of damages incurred by employees related to the Phoenix pay system. Between 2017 and 2019, this committee worked independently from the collective bargaining tables.

On June 12, 2019, an agreement was reached between the Employer and 15 Bargaining Agents on Phoenix damages (Exhibit #4). The PSAC did not agree to the terms of the agreement, which includes up to five days of paid leave, and compensation for monetary and non-monetary losses.

This agreement settled the damages portion of the pending recourse by these Bargaining Agents and their members following the filing of unfair labour complaints, as well as policy and individual grievances.

The Employer is open to continuing discussions with the PSAC to conclude an agreement on Phoenix damages, recognizing that PSAC employees should be compensated for the damages incurred related to the Phoenix pay system. However, the Employer respectfully submits that Phoenix-related damages should not influence this Committee’s deliberations. This issue is pending resolution at a different forum, and in the event that the parties fail to reach an agreement, the FPSLREB is the appropriate forum for third-party resolution.

Part I: status of negotiations

- In this section

- 1.1 Negotiations in the federal public service

- 1.2 Common items negotiated for the core public administration and separate agencies

- 1.3 Negotiations with the Operational Services (SV) Group

- 1.4 Bargaining Agent proposals

- 1.5 Employer proposals

- 1.6 Common proposals

- 1.7 Damages related to the Phoenix pay system

1.1 Negotiations in the federal public service

The Government of Canada is committed to bargaining in good faith with all federal public sector Bargaining Agents. The government’s approach is to negotiate agreements that are reasonable for employees, Bargaining Agents and Canadian taxpayers.

Through meaningful and good faith negotiations, the Government of Canada has reached 34 agreements during this round of bargaining, covering more than 65,000 employees in the federal public service. This includes settlements with 15 different Bargaining Agents representing 17 bargaining units in the CPA and 17 employee groups in separate agencies.

Core public administration

Since the spring of 2018, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) has been engaged in negotiations on behalf of the Treasury Board, the Employer of the CPA, with more than 11 Bargaining Agents for the renewal of collective agreements representing more than 175,000 employees. Footnote 2 Footnote 3

TBS successfully concluded collective agreements for 17 CPA groups with 11 Bargaining Agents. These 17 collective agreements cover employees represented by some of the largest Bargaining Agents, including the PIPSC, CAPE and ACFO.

Table 1 below lists the bargaining units with new collective agreements, their union affiliation and population as of March 2018.

Table 1: Bargaining units with new collective agreements, CPA

CPA bargaining unit Bargaining Agent Population EC: Economics and Social Science Services CAPE 14,777 SP: Applied Science and Patent Examination PIPSC 7,647 AV: Audit, Commerce and Purchasing PIPSC 5,783 FI: Financial Management ACFO 4,776 NR: Architecture, Engineering and Land Survey PIPSC 3,541 SH: Health Services PIPSC 3,100 LP: Law Practitioner AJC 2,832 RE: Research PIPSC 2,630 FS: Foreign Service PAFSO 1,512 EL: Electronics IBEW 1,059 TR: Translation CAPE 811 SR(W): Ship Repair West FGDTLCW 642 SR(E): Ship Repair East FGDTLCE 590 RO: Radio Operations UNIFOR 272 UT: University Teaching CMCFA 180 SR(C): Ship Repair Chargehands FGDCA 52 AI: Air Traffic Control UNIFOR 9 Total population 50,195 Separate agencies

The 27 active separate agencies listed in Schedule V of the Financial Administration Act conduct their own negotiations for unionized employees. They are distinct from the CPA; they have different job duties and specific wage levels according to their business purpose. The largest separate agencies include the CRA, Parks Canada, and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

The CPA and separate agencies share many of the same bargaining agents, including the PSAC and PIPSC.

As part of the federal public administration, separate agencies follow the same broad government objectives; they are committed to negotiating agreements in good faith that are fair and reasonable for employees, bargaining agents and Canadian taxpayers.

During the current round of negotiations, six separate agencies have concluded 17 collective agreements with four bargaining agents representing 17,000 employees. Table 2 below lists the separate agencies, and bargaining units with new collective agreements, their union affiliation and population.

Table 2: Bargaining units with new collective agreements, Separate Agencies

Separate agency Bargaining Agent Bargaining unit Population Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) PIPSC Audit, Financial and Scientific (AFS) 11,447 Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) PIPSC Nuclear Regulatory Group (NUREG) 730 Canada Energy Regulator (formerly the National Energy Board (NEB)) PIPSC All Unionized Employees 377 National Film Board (NFB) PIPSC Administrative and Foreign Services Group 174 Scientific and Professional Group SGCT/CUPE Technical Group 103 CUPE Administrative Support Group 88 Operation Group National Research Council Canada (NRC) RCEA Administrative Services Group (AS) 244 Administrative Support Group (AD) 268 Computer Systems Administration (CS) 214 Operational Group (OP) 62 Purchasing and Supply Group (PG) 22 Technical Group (TO) 999 PIPSC Information Services (IS) 64 Library Services (LS) 43 Research Officer / Research Council Officer (RO/RCO) 1,596 Translator Group (TR) 8 Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) PIPSC Professional Employees Group (PEG) 551 Total population 16,990 1.2 Common items negotiated for the core public administration and separate agencies

The 34 agreements reached in the CPA and separate agencies include some common items, including basic economic increases and other monetary and non-monetary elements.

Annual economic increases over four years

- Year one: 2%

- Year two: 2%

- Year three: 1.5%

- Year four: 1.5%

Group-specific wage adjustments of approximately 1% over the four years of the agreements

For most of the groups, such as the NR and the SP groups represented by PIPSC, these improvements take the form of wage adjustments staggered over two years: 0.8% in year one and 0.2% in year two.

Some other groups, such as the FS group represented by PAFSO, received different targeted measures to address their specific needs, but the overall value of these group-specific improvements was approximately 1% over the four years of their agreements.

An MOU on the implementation of collective agreements

At the outset of this round of negotiations, the government made it clear to all Bargaining Agents that retroactivity and the implementation of the agreements were key issues given the ongoing challenges surrounding the Phoenix pay system and the implementation of the agreements concluded during the previous round of bargaining.

In the spring of 2019, the government developed a new methodology for the calculation of retroactive payments to facilitate its implementation. The government also negotiated extended implementation timelines, reasonable compensation for employees in recognition of the extended timelines and accountability measures. All of these measures are outlined in the MOU that is included in all 34 federal public service agreements. The new methodology has proven to date that the timelines agreed to through the MOU are being respected (Exhibit #5).

The key elements of the MOU include the following:

- Changes to existing or new compensation elements that do not require manual intervention from compensation advisors will be implemented within 180 days after the signature of the agreements.

- Changes to existing or new compensation elements that require manual intervention from compensation advisors will be implemented within 560 days after the signature of the agreements.

- All employees in the group covered by a new agreement will receive a $400 lump-sum payment upfront in recognition of extended implementation timelines.

- Employees for whom the implementation takes longer than 180 days will receive a $50 payment for each 90-day delay beyond the initial implementation period of 180 days, to a maximum of $450 per employee.

- Employees for whom the implementation takes longer than 180 days will be notified within 180 days after the signature of the agreement.

Given the pay and HR systems in place and the ongoing challenges, the government of Canada has no flexibility to implement agreements on a different basis that what is included in the negotiated MOU. Agreeing to a different implementation process and timelines would represent bad faith bargaining on behalf of the government, as it would be agreeing to something that it cannot fulfill.

Extended/new leave provisions

Several improvements were negotiated with the other bargaining units that provide for new and improved leave entitlements for employees:

- Up to 10 days of paid leave per year for situations of domestic violence.

- Extension of the parental leave without pay provision to allow employees to choose an extended leave period, with the top-up allowance paid by the Employer spread over the longer period, and extension of the maximum payable top-up period to cover paternity leave (Quebec) and shared parental leave (rest of Canada).

- Caregiving leave without pay of up to 35 weeks to allow employees to benefit from critical illness and compassionate care benefits available under the Employment Insurance program.

- Improvements to the definition of family – specifically the introduction of a person who stands in the place of a relative for the employee, whether or not there is any degree of consanguinity between such person and the employee. This improves access to bereavement leave with pay, leave with pay for family-related responsibilities, and leave without pay for the care of family.

The Employer proposes a settlement for the SV group that contains improvements that are similar to those negotiated in the rest of the federal public service. The Employer recommends that the Commission provide recommendations that are aligned with the recently established pattern.

As per the Replication Principle, the Employer suggests that the Commission’s report replicate the result, as closely as possible, to that which would have been achieved had the parties negotiated a settlement on their own. The Employer submits that the Bargaining Agent’s proposed economic increases do not reflect what the parties would have bargained.

The Employer is of the view that there is no evidence to justify providing wage increases for the SV group that exceed the cumulative increases that employees in the 17 CPA groups and the 17 federal separate agency groups will receive over a four-year agreement. There is no rationale supporting the significantly higher economic increases sought by the PSAC, in addition to market adjustments between 9% and 39%.

1.3 Negotiations with the Operational Services (SV) Group

In this round of bargaining, PSAC and TBS officials were engaged in six (6) negotiation sessions for the SV group between May 2018 and May 2019. The parties were also engaged in three (3) negotiations sessions at a separate bargaining table mandated to negotiate proposals that are common across the four (4) bargaining units represented by the PSAC: Program and Administrative Services (PA), Technical Services (TC), Education and Library Science (EB), Operational Services (SV), between June 2018 and December 2018.

As noted in Table 3 below, the parties “agreed in principle” to the following items during negotiations, which are all administrative, or housekeeping in nature.

“Public Service Labour Relations Act“ with “Federal Public Sector Labour Relations Act”; and

“Federal Public Service Labour Relations Board” with “Federal Public Sector Labour Relations and Employment Board.”

Clauses 2.01, 37.11, 37.12, 67.09, 68.01

Appendix A (6.01),

Appendix B: Annex E (3.4), (4.4), (6), (8)

Appendix B: Annex H (1),

Appendix B: Annex J (5),

Appendix C (2.05),

Appendix D (3.06),

Appendix F (3.02), (5.10)

Appendix G (1.01), (2.03), (3.04), (14), (16),

Appendix G: Annex B (7),

Appendix G: Annex C (6.04),

Appendix G: Annex D (7.01),

Appendix G: Annex E (1), (4), (6), (10),

Appendix G: Annex J

Appendix I (English version only)Delete references to “cash” and replace with “payment.”

“Part II of Schedule I of the Public Service Staff Relations Act” with “Schedule V of the Financial Administration Act.”

The PSAC declared impasse and filed for the establishment of a PIC on December 11, 2018. The Chairperson of the FPSLREB advised the parties on

January 29, 2019, that she was not recommending the establishment of the PIC and encouraged the parties to resume negotiations. In her decision, the Chairperson indicated that she was not satisfied that the parties had bargained sufficiently and seriously, nor was she convinced that impasse had been reached.After additional negotiations meetings in the winter and spring of 2019, the PSAC submitted a request to the Board on May 7, 2019, for the reactivation of their request, which was granted by the Chairperson.

1.4 Bargaining Agent proposals

The Bargaining Agent has submitted an extensive list of proposals during this round of bargaining. The union proposals include above pattern economic increases, as well as increases to leave provisions, new allowances, and other monetary and non-monetary elements that currently do not exist in the SV agreement and/or in other collective agreements in the CPA.

The PSAC has tabled 23 proposals that are common to all PSAC groups, including two additional designated paid holidays per year, and increased vacation leave entitlements.

The PSAC also tabled 55 changes that are specific to the SV group. These proposals deal with 22 collective agreement articles and six (6) appendices, in addition to new articles and memoranda and/or allowances.

As noted in Table 4 below, the PSAC monetary proposals, which include annual economic increases of 3.25% over three years totalling 10.33%, are equivalent to an overall increase of 37.87%, compared to the 2018 SV wage base. This overall increase does not include certain proposals that could not be costed by the Employer due to data availability issues.

Appendix B, GL: amend the calculation for Height pay allowance from:

“25% of the employee’s basic hourly rate of pay on a pro rata basis for actual time worked” to “an additional one half (1/2) their straight-time rate of pay for every fifteen (15) minute period, or part thereof worked”

- 4 weeks’ vacation upon appointment (instead of current 3 weeks)

- 4 weeks and 2.8 days at 8 years (instead of current 4 weeks at 8 years)

- 4 weeks and 4.2 days at 16 years (instead of current 4 weeks and 2.8 days at 16 years)

- 5 weeks at 17 years (instead of current 4 weeks and 4.2 days at 17 years)

- 5 weeks and 2.8 days at 18 years (instead of current 5 weeks at 18 years)

- 6 weeks at 27 years (instead of current 5 weeks and 2.8 days at 27 years)

- 7 weeks at 28 years (instead of current 6 weeks at 28 years)

- Full-time station

- In 1 and 2 man person stations: from $2,237 to $2,800

- In 4 man person stations: from $1,917 to $2,400

Article 27: Shift and Weekend Premiums

- increase the shift premium from $2.00 to $3.00 per hours for all hours worked, including overtime hours, between 4:00 pm and 8:00 pm

- increase the weekend premium from $2.00 to $3.00 for all hours worked on Saturday or Sunday, including overtime hours

- all school or daycare closures,

- attending appointments with legal or financial professionals and

- to allow for visits with a terminally ill family member

Note: Due to data availability, some proposals were not costed and were not included in this table, including:

- 9% wage adjustment for the GL-AMW and GL-GHW subgroups

- 21% wage adjustment for the SC-EQO subgroup

- Restructures to the LI-01 and LI-02 rates

- Amendments to the Dirty Work allowance in Appendix B, Appendix D and Appendix G

- Expansion of shift premium eligibility in Appendix D

- New overtime provisions in Appendix G – Annex E

- New parking cost provisions in Appendix G – Annex G

1.5 Employer proposals

The Employer proposes to negotiate improvements for the SV group that are similar to those negotiated to date with 34 groups in the federal public service.

The Employer’s detailed position on each outstanding items can be found in Parts III and IV of the Employer’s brief.

The Employer’s monetary proposals, with the associated costs, are included in Table 5 below.

Table 5: Employer’s monetary proposals

Employer monetary proposals Ongoing cost % of wage base Common proposals 10 days of paid leave for domestic violence $94,671 0.01% Expanded provisions for definition of family (various articles) $411,612 0.06% Parental leave without pay (standard/extended period) Cost neutral 0.00% Caregiving leave without pay related to critical illness $520,278 0.07% SV-Specific proposals Pattern economic increases over four years: 2.0%, 2.0%, 1.5%, and 1.5% $50,880,482 7.18% An additional 1% for group-specific adjustments $7,496,919 1.06% Total $59,403,962 8.39% The Employer’s proposal also include the MOU on the implementation of the collective agreement negotiated with all the groups in the CPA and separate agencies.

Given the high volume of outstanding proposals submitted by the Bargaining Agent, the Employer requests that the PSAC target a limited number of proposals that take into account the current collective bargaining landscape and recent negotiation outcomes with other federal public service Bargaining Agents. The large number of proposals make it challenging for the parties to identify and focus their work on key priorities; a more limited number of proposals is expected to meaningfully improve the likelihood of settlement. The Employer respectfully suggests that the Commission issue a direction in that regard and direct the parties to return to negotiations with a reduced number of proposals, prior to the issuance of the Commission’s report.

1.6 Common proposals

Twenty-three provisions, listed below, have been identified jointly by the parties as common proposals that apply to all four tables (PA, SV, TC and EB) currently in the PIC process.

On November 25, 2019, the Employer and the Bargaining Agent agreed that it was appropriate to make representations on these provisions only once and to do so during the PIC process for the PA group. This avoids unnecessary duplication in the respective submissions for the four groups, and limits the risk of having different recommendations on the same topics.

- Article 10: information

- Article 11: check-Off

- Article 12: use of Employer facilities

- Article 13: Employee representatives

- Article 14: leave with or without pay for Alliance business: cost recovery

- Article 17: discipline

- Article 20: sexual harassment

- Article 24: technological change

- Article 30: designated paid holiday

- Article 34: vacation leave with pay

- Article 35: sick leave with pay

- Article 40: parental leave without pay

- Article 42: compassionate care and caregiving leave

- Article 57: employee performance review and employee files

- Article 65: pay administration

- New article: domestic violence leave

- New article: protections against contracting out

- Appendix D: workforce adjustment

- Appendix F: Memorandum of Understanding Between the Treasury Board of Canada and the Public Service Alliance of Canada with Respect to Implementation of the Collective Agreement

- Appendix M: Memorandum of Understanding between the Treasury Board and the Public Service Alliance of Canada with respect to Mental Health in the Workplace

- Appendix N: Memorandum of Understanding between the Treasury Board and the Public Service Alliance of Canada with respect to Child Care

- Appendix O: Memorandum of Agreement on Supporting Employee Wellness

- New Appendix: Memorandum of Understanding Between the Treasury Board of Canada and the Public Service Alliance of Canada (RCMP)

1.7 Damages related to the Phoenix pay system

In May 2017, the PSAC and other CPA Bargaining Agents chose to create and mandate a joint senior-level Employer-Union Phoenix subcommittee to resolve the issue of damages incurred by employees related to the Phoenix pay system. Between May 2017 and June 2019, this committee worked independently from the collective bargaining tables.

On June 12, 2019, an agreement was reached between the Employer and 15 Bargaining Agents on Phoenix damages. The PSAC did not agree to the terms of the agreement, which includes up to five days of paid leave, and compensation for monetary and non-monetary losses. This agreement settled the damages portion of the pending recourses by these Bargaining Agents and their members following the filing of unfair labour complaints, as well as policy and individual grievances.

The Employer is open to continuing discussions with the PSAC to conclude an agreement on Phoenix damages, recognizing that PSAC employees should be compensated for the damages incurred related to the Phoenix pay system. However, the Employer respectfully submits that Phoenix-related damages should not influence this Committee’s deliberations. This issue is pending resolution at a different forum, and in the event that the parties fail to reach an agreement, the FPSLREB is the appropriate forum for third-party resolution.

Part II: considerations

- In this section

- 2.1 Recruitment and retention

- 2.2 External comparability

- 2.3 Internal relativity

- 2.4 The state of the economy and the government’s fiscal situation

- 2.5 Replication principle

- 2.6 Total compensation

In its approach to collective bargaining and the renewal of collective agreements, the Employer’s goal is to ensure fair compensation for employees and, at the same time, to deliver on its overall fiscal responsibility and commitments to the priorities of the government and Canadians.

Section 175 of the FPSLRA outlines four principles for consideration by public interest commissions:

- Recruitment and retention

- a. the necessity of attracting competent persons to, and retaining them in, the public service in order to meet the needs of Canadians;

- b. the necessity of offering compensation and other terms and conditions of employment in the public service that are comparable to those of employees in similar occupations in the private and public sectors, including any geographic, industrial or other variations that the public interest commission considers relevant;

- c. the need to maintain appropriate relationships with respect to compensation and other terms and conditions of employment as between different classification levels within an occupation and as between occupations in the public service;

- d. the need to establish compensation and other terms and conditions of employment that are fair and reasonable in relation to the qualifications required, the work performed, the responsibility assumed and the nature of the services rendered; and

- e. the state of the Canadian economy and the Government of Canada’s fiscal circumstances

In addition, the Employer appeals to replication as a guiding principle to set compensation and suggest that the Commission consider all elements of total compensation when making its recommendations for the SV group.

2.1 Recruitment and retention

TBS sets compensation levels that enable it to recruit and attract qualified and motivated employees. Recruitment and retention indicators show that the SV group is relatively healthy and provides no evidence that increases above the established pattern is needed to recruit and retain employees.

The public service went through a restraint period from 2011–12 to 2015–16. The data presented in this section reflect the Government of Canada’s restraint measures that affected employment. During this period, the Government of Canada undertook the Deficit Reduction Action Plan, strategic and operating reviews, and implemented an operating budget freeze through to 2015–16. Footnote 4 These measures had direct effects on hiring and employment levels across the Government of Canada. The data tables below present information for the SV occupational groups in comparison to the average for the core public administration.

Table 6 shows the SV group population over the last five (5) fiscal years. Over the reference period, the FR, GS and SC groups have all shown strong growth, while the populations for the GL and HP have stabilized over the same period. These are the types of changes in population that one would expect coming out of a period of restraint. It is also important to note that while the HS group experienced a significant decrease in population over the reference period, this was due to the transfer of Ste-Anne’s hospital employees to the Government of Quebec in 2016, and not due to any recruitment or retention problems.

Source: Incumbent file

- Figures include employees working in departments and organizations of the core public administration (FAA Schedule I and IV).

- Figures include all active employees and employees on leave without pay (by substantive classification) who were full- or part-time indeterminate and full- or part-time seasonal.

Table 7 shows that the hirings were very healthy for the SV groups since 2013–14. Hires for the GS and HP groups were very strong over the reference period, while the GL group hires have increased by almost 3 times since 2013–14. The SC group has demonstrated even stronger hires being more than enough to compensate for separations shown in Table 8. While the hiring rate for the FR group was lower than the CPA average, it is important to keep in mind that separations have been extremely low for this group and departments have not needed to hire at the same rate as other groups. Finally, the volatile hiring rate for the HS group can once again be explained by the departure of employees to the Government of Quebec.

Source: PSC Appointments file

- Figures include employees working in departments and organizations of the core public administration (FAA Schedule I and IV).

- Figures include all active employees and employees on leave without pay (by substantive classification) who were full- or part-time indeterminate and full- or part-time seasonal.

- External hiring includes hires from outside the CPA. It also includes employees whose employment tenure changed from casual, term or student to indeterminate or seasonal.

- Internal hiring includes hires to the group from other groups within the CPA.

- Total hiring rates are calculated by dividing the number of external and internal hires in a given fiscal year by the average number of employees.

Table 8 shows separation rates for the SV bargaining unit from 2013–14 to 2017–18. The FR group has demonstrated extremely low separation rates that are consistently below that of the CPA average. In terms of the remaining groups, the GL, GS and HP have had separation rates that are comparable to that of the CPA average while the SC group has had separations slightly above. As mentioned earlier, the higher separation rates for the HS group were due to the transfer of some employees to the Government of Quebec.

As noted in Table 8, the SV group has experienced very few employees leaving the public service due to non-retirement, with the majority of groups experiencing a decline for this statistic. This further demonstrates that the federal government continues to offer attractive terms and conditions, stable employment and very competitive wages which makes it a highly sought-after establishment for employment.

Voluntary non-retirements Voluntary retirements Involuntary Unspecified Voluntary non-retirements Voluntary retirements Involuntary Unspecified Voluntary non-retirements Voluntary retirements Involuntary Unspecified Voluntary non-retirements Voluntary retirements Involuntary Unspecified Voluntary non-retirements Voluntary retirements Involuntary Unspecified Voluntary non-retirements Voluntary retirements Involuntary Unspecified Internal separations Voluntary non-retirements Voluntary retirements Involuntary Unspecified Voluntary non-retirements Voluntary retirements Involuntary Unspecified- Figures include employees working in departments and organizations of the core public administration (FAA Schedule I and IV).

- Figures include all active employees and employees on leave without pay (by substantive classification) who were full- or part-time indeterminate and full- or part-time seasonal.

- External separations are separations to outside the CPA. Voluntary non-retirement separations include resignation from the CPA for: outside employment, return to school, personal reasons, abandonment of position; it also includes separation to a Separate Agency. Voluntary retirement separations include all retirements due to illness, age, or elective. Involuntary separations include resignation under Workforce Adjustment, discharge for misconduct, release for incompetence or incapacity, cessation of employment (failure to appoint), dismissed by Governor-in-Council, layoff, rejected during probation, and death.

- Internal separations are separations from the group to other groups within the CPA.

- Total separations rates are calculated by dividing the number of external and internal separations in a given fiscal year by the average number of employees.

Table 9 presents job advertisement figures for the SV groups. The analysis shows that the total number of screened-in candidates per job advertisement has been consistent high over the 5-year period, providing departments with a large pool of qualified applicants.

It is important to note that highly specialized groups, such as the SV group, have a more limited pool to draw from, compared to groups requiring less specialized skills, such as the PA group. This explains the results shown below.

- Figures include applications to external job advertisements from departments and organizations of the core public administration (FAA Schedule I and IV).

- Data are for closed advertisement. Cancelled advertisements are excluded.

- Screened-In applications are those that meet the essential criteria of the advertisement.

Public Service Employee Survey results for the SV bargaining unit

The Public Service Employee Survey results include certain indicators for measuring retention and overall job satisfaction.

Table 10 shows that the majority of employees in the SV group like their job. The federal government continues to offer attractive terms and conditions, stable employment and very competitive wages, which makes it a highly sought-after establishment for employment.

This further demonstrates that the Employer’s wage offer, replicating the pattern negotiated with 34 other groups in the federal public service, is very reasonable.

Table 10: Overall job satisfaction

Q14. Overall, I like my job. Positive (%) 2018 SV FR 82 GL 80 GS 81 HP 82 HS 91 LI 82 PR 93 SC 88 Public service average 80 Table 11 shows that employees in the SV group are less likely to leave their position over the next two years, as compared to the public service average. This once again points to evidence that SV employees have an overall high sense of job satisfaction and that they are not actively looking to leave their current position.

Table 11: Intention to leave current position

Q46. Do you intend to leave your current position in the next two years? 2018 PSES survey Yes (%) No (%) Not Sure (%) SV FR 12 60 28 GL 16 52 32 GS 21 45 34 HP 14 57 29 HS 11 48 41 LI 25 62 14 PR 8 85 7 SC 21 50 29 Public service average 27 39 35 2.2 External comparability

This section compares SV group pay rates to those offered in the external market. The Government of Canada’s stated objective is to provide compensation that is competitive with, but not leading, compensation provided for similar work in relevant external labour markets. TBS reviews labour market trends nationally and it commissions third-party human resources experts to conduct research at the occupational group level. National trends guide compensation decisions.

This section will demonstrate that SV wages are competitive with the external labour market.

Summary of external wage studies

In 2019, Mercer Canada LLC completed a study to evaluate the competitiveness of its base salary levels for 18 positions in the SV group relative to the external market (a copy of the final report can be found in Exhibit #6). For the selected positions, secondary research salary surveys from the HR firms Mercer, Towers Watson, and Morneau Shepell were used to conduct the market analysis. Matches for these 18 benchmark positions were determined based on job content and professional judgment, as survey capsule descriptions are typically brief relative to organizational descriptions. As a rule of thumb, positions are considered a “good match” if at least 80% of the role is represented in the survey position capsule description.

There were five (5) positions where Mercer was unable to provide market data due to insufficient data from the salary surveys or no appropriate job match (Firefighter, Fire Inspector, Pipefitter, Automobile/Heavy Duty Mechanic, and Construction/Maintenance Supervisor).

TBS’s incumbent data was compared to the 50th percentile of the market using the maximum salary range for its annualized base salary. The maximum level of a salary range is a good indicator of the expected salary of federal government employees. Generally, federal public sector base pay practices are calibrated such that employees will achieve the maximum base salary rate of pay (job rate) of their salary band based on a combination of tenure and performance. External to the public sector at any given level, the 50th percentile of a defined labour market, typically represents the expected salary for “fully competent” job performance. Progression beyond the 50th percentile midpoint is generally reserved for a high relative performance and advanced competency growth. The choice of the 50th percentile as an acceptable benchmark is consistent with TBS’s key guiding compensation principle that TBS wants compensation in the public service to be competitive with, but not lead, relevant external labour markets that provide similar work.

Compensation within plus or minus 10% of TBS’s target market positioning are generally considered to be within competitive norms and market-aligned. By assuming a single competitive rate, one would impose too high a level of precision on an analysis that requires subjective decisions in defining and comparing work across organizations.

Overall, Table 12 indicates that SV wages are either competitive with or leading the market for all but one position. However, the one position that lagged the market, Driver, Heavy vehicle (GL-MDO-05), when comparing TBS 2017 rates to 2018 markets rates; applying the Employer’s first year proposal would shift the GL-MDO-05 within the competitive range. In addition, adjusting the wages by the Employer’s proposal for the first year would shift the Construction Labourer (GL-ELE-03), Building Systems Maintenance Technician (GL-MAM-08) and Cook (GS-FOS-06) ahead of the market, while improving the competitiveness for the remainder of the positions.

Table 12: SV wage study results

Compensation data in $000s

Actual base salary Stream TBS position Classification level TBS maximum salary P50 ($) TBS maximum vs. market P50 Firefighters Firefighter FR-01 $77,60 n/a n/a Fire Inspector FR-02 $81,70 n/a n/a Compensation data in $ hourly

Actual hourly rate Stream TBS position Classification level TBS maximum rate P50 ($) TBS maximum vs. market P50 General Labour and Trades Construction Labourer GL-ELE-03 $22,30 $20,51 9% Driver, Heavy Vehicle GL-MDO-5 $24,63 $27,84 -12% Building Systems Maintenance Technician GL-MAM-08 $29,13 $26,66 9% Painter / Sign Painter GL-PCF-07 $30,32 $32,11 -6% Carpenter GL-WOW-09 $30,68 $32,82 -7% HVAC / Mechanical Technician GL-MAM-10 $35,30 $34,48 2% Pipefitter GL-PIP-09 $32,27 n/a n/a Automobile / Heavy Duty Mechanic GL-VHE-10 $33,47 n/a n/a Construction/Maintenance Supervisor GL-COI-11/C3 $39,02 n/a n/a Electrician GL-EIM-11 $35,46 $37,19 -5% Sheet Metal Worker GL-SMW-10 $35,62 $35,77 0% General Services Building Cleaner GS-BUS-02 $20,26 $21,30 -5% Food Service Helper GS-FOS-02 $20,26 $19,58 3% Storeperson GS-STS-04 $24,90 $26,69 -7% Cook GS-FOS-06 $28,65 $26,46 8% Heating, Power and Stationary Plant Operations Shift Engineer (non-supervisory) HP-04 $35,19 $29,59 19% As shown in Table 13, Mercer also performed a joint wage study with the PSAC to determine market relativity for the SC positions within the SV group (a copy of the final report can be found in Exhibit #7). Primary research was completed based on the TBS benchmark roles for the SC group. The results showed that the SC group currently have wages that are comparable with the market.

Table 13: SC wage study results

Compensation data in $Actual base salary Stream TBS position Classification level TBS Maximum salary P50 ($) TBS maximum vs. market P50 Ships Crews Deckhand SC-02 $54,072 $54,140 0% Boatswain SC-05 $59,496 $56,420 5% Engine Room Assistant SC-03 $55,824 $55,968 0% Steward STD-01 $52,896 $50,450 5% The results of the Mercer studies further support the Employer’s position that exceeding 2.0%, 2.0%, 1.5% and 1.5% over four years and deviating from the current pattern established with the core public administration’s represented population is unwarranted.

Analysis of SV pay study results from 2015 and 2019

This section explains how the 2014 collective bargaining settlement provided sufficient funding to fully address the market gaps identified in the joint 2015 study. The 2019 study shows that SV group occupations are broadly competitive with their market comparators, examined as a whole. Consequently, the 1% available for group-specific measures is sufficient to address any outstanding gaps, if it is the PSAC’s decision to do so.

The section reviews methodological issues related to the use of pay studies in determining wage increases.

The 2015 joint Hay study

In February 2015, a joint compensation review with the PSAC was completed by the Hay group. The study surveyed 21 SV positions agreed upon by both parties.

The survey consisted of primary research inviting 360 organizations to participate. The invitees were either large private sector corporations or public sector organizations.

The Hay group developed a custom survey with data elements for each of the benchmark positions, which were sent to the potential participants. Participating organizations completed the surveys and returned the information directly to the contractor. In total, 47 organizations provided responses for 23,517 incumbent positions and 17 occupations. The Hay group then vetted the data, as well as the job matching information, and followed up where necessary based on their professional judgment. The data was then aggregated and market wage estimates were determined.

As indicated in Table 14, the 2015 Joint Hay Study results showed that wages for some SV subgroups were behind their external comparators, with many being within a plus or minus 10% range. The results also indicated that some SV subgroups were ahead of their external comparators.

* Note the GL-MAM refrigeration HVAC technicians received an $8,000 HVAC Allowance

A critical issue between the parties, in determining the nature of the market gap, was whether the results were incumbent-weighted or organization-weighted. As noted in Table 14, the difference in results between incumbent-based and organization-based weighting in the 2015 Joint Hay Study were mixed. For 8 of the 17 occupations, the incumbent-weighted results showed higher external salaries than the organization-weighted data. However, for two occupations, salaries of external comparators were almost 70% higher on an incumbent-weighted basis than an organization-weighted basis (HVAC Technician and Stationary Engineer).

Details on the two methodologies are provided below:

- Under incumbent-weighting, each job response was counted equally in calculating average wages for external comparators. The difficulty with this approach is that organizations that provided multiple responses for a particular occupation were over-represented in calculating average wages, as compared to other organizations, even though their relative importance was the same. In other words, two similar organizations could be provided significantly different weight in determining results, as a result of the manner in which they completed the survey.

- Under organization-weighting, the wage rates for each occupation within an organization were given equal weight in determining average external wages, irrespective of the number of individual responses an organization provided for the occupation.

The Employer based its analysis on the organizational-weighted results, on the basis that these results were more representative of the external labour market, this approach reduced the impact of outlying data and it avoided individual organizations having an undue influence on the results. Moreover, organization-weighted results are the generally accepted industry standard.

2014 round of negotiations

To address the results of the 2015 Joint Hay study, the Employer allocated an amount for wage adjustments in the 2014 round of bargaining based on a weighted average of the wage gap across subgroups, taking into consideration occupations that were both above and below market comparators. Footnote 5 Taking account of the annual economic increases as part of the pattern settlement, the allocated mandate was sufficient to allow wages for all subgroups covered by the study to be aligned to their external comparators.

A tentative settlement was reached by the parties on February 4, 2017, with pattern economic increases for the SV group of 1.25% per year over four years, which was consistent with the rest of the core public administration, and wage increases to address the gaps identified by the Employer’s analysis of the study.

Market adjustments of 15% were provided to the FR and the HP groups, which were the highest increases in the 2014 round of bargaining. The GL-VHE group received a 9% market adjustment, the GL-EIM group received a market adjustment of 6% and the GL-MAM group received a market adjustment of 2.5%, plus an annual HVAC allowance of $8,000. Groups that had results with rates higher than the market also received a wage adjustment in year three of the agreement. A complete listing of the market and wage adjustments provided in the 2014–2018 round can be found in Exhibit #8.

It should also be noted that the union negotiated a 5% wage adjustment for the SC group even though they were not included in the 2015 Joint Hay Study results. The effect of this was to divert a significant amount of funds that could have been otherwise used to fully close the market gap identified by the study for other subgroups. In effect, the union chose to prioritize internal relativity considerations over external comparability.

The 2014 negotiations were intended to provide a final resolution to the external comparator market gaps identified in the 2015 Joint Hay Study. The parties acknowledged this in the settlement report in noting that wage adjustments were “to resolve issues identified in the March 30, 2015, TBS/PSAC 2014 compensation survey result” (Exhibit #8).

The 2019 Mercer study

In 2019, the Employer engaged Mercer Canada for a wage study using the same positions included in the 2015 Joint Hay Study (minus the SC groups). Similar to the latest PA and TC wage studies, this study was done using secondary research and compared SV wages with the external market.

Secondary research such as this is common practice in determining compensation in the market and has often been used by the Employer in collective bargaining, arbitration and conciliation. Recently, secondary research was used in a joint wage study with the Electronics (EL) Group (International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW)) and led to a deal in this current round of bargaining.

The research used in the 2019 Mercer study contains 2018 market data from the Mercer Benchmark Database, Willis Towers Watson Survey, and the Morneau Shepell Survey. Mercer matched benchmark positions based on job content and professional judgment. The results of this survey are outlined in Table 15.

Table 15: 2019 SV wage study results

Compensation data in $000s

Actual base salary Stream TBS position Classification level TBS maximum salary P50 ($) Converted annual TBS maximum vs. market P50 Firefighters Firefighter FR-01 $77,60 n/a n/a n/a Fire Inspector FR-02 $81,70 n/a n/a n/a Compensation data in $ hourly

Actual hourly rate Stream TBS position Classification level TBS maximum rate P50 ($) Converted annual TBS maximum vs. market P50 General Labour and Trades Construction Labourer GL-ELE-03 $22.30 $20.51 $42,805 9% Driver, Heavy Vehicle GL-MDO 5 $24.63 $27.84 $58,103 -12% Building Systems Maintenance Technician GL-MAM-08 $29.13 $26.66 $55,640 9% Painter/Sign Painter GL-PCF-07 $30.32 $32.11 $67,015 -6% Carpenter GL-WOW-09 $30.68 $32.82 $68,497 -7% HVAC / Mechanical Technician GL-MAM-10 $35.30 $34.48 $71,961 2% Pipefitter GL-PIP-09 $32.27 n/a n/a n/a Automobile/Heavy Duty Mechanic GL-VHE-10 $33.47 n/a n/a n/a Construction/Maintenance Supervisor GL-COI-11/C3 $39.02 n/a n/a n/a Electrician GL-EIM-11 $35.46 $37.19 $77,617 -5% Sheet Metal Worker GL-SMW-10 $35.62 $35.77 $74,653 0% General Services Building Cleaner GS-BUS-02 $20.26 $21.30 $44,454 -5% Food Service Helper GS-FOS-02 $20.26 $19.58 $40,864 3% Storeperson GS-STS-04 $24.90 $26.69 $55,703 -7% Cook GS-FOS-06 $28.65 $26.46 $55,223 8% Heating, Power and Stationary Plant Operations Shift Engineer (non-supervisory) HP-04 $35.19 $29.59 $61,756 19% The results in Table 15 show that the HP-04 position is currently leading the market while the remaining positions other than the GL-MDO-05 were deemed to be comparable. It is important to note that the study shows that TBS wages are highly competitive with the market even though the study compares 2017 TBS wages to market data from 2018. Adjusting for this would move the GL-MDO-05 into the comparable range.

There were five (5) positions where Mercer was unable to provide results due to insufficient data.

Comparing the 2015 Joint Hay study and the 2019 Mercer study

Table 16 shows a comparison between the 2015 Joint Hay and the 2019 Mercer studies (using an organization-weighted approach). The results of the 2019 Mercer study are consistent with those of the 2015 Hay study. External wages in the 2019 Mercer study are about 11% higher than the 2015 Hay study, which is modestly higher than average wage growth over the 2015 to 2019 period. Nevertheless, there are significant differences in individual occupational results, which can be expected in small sample studies.

The key conclusion is that the Mercer study is not biased downward relative to the 2015 joint study. If anything, it is, on average, more favourable to the union than the 2015 study.

Table 16: Comparison of 2015 and 2019 wage studies

Study position Job group level Hay 2015 study Mercer 2019 study 2015 Hay vs. 2019 Mercer CPA salary Annual salary: organization-weighted / P50 2018 annual salary

organization-weighted / P50% difference 2017 annual salary 1. Fire Fighter FR01 $81,500 n/a n/a n/a 2. Fire Lieutenant / Chief FR02 $102,200 n/a n/a n/a 3. Construction / Maintenance Supervisor GLCOI11 $80,800 n/a n/a n/a 4. Electrician GLEIM11 $66,500 $77,617 16.7% $74,006 5. General Labourer / Trades Helper GLELE03 $47,100 $42,805 -9.1% $46,541 6. Building Systems Maintenance Technician GLMAM08 $64,100 $55,640 -13.2% $60,795 7. Driver, Heavy Vehicle GLMDO05 $45,900 $58,103 26.6% $51,404 8. Painter / Sign Painter: Construction GLPCF07 $57,800 $67,015 15.9% $63,279 9. Plumber / Pipefitter GLPIP09 $63,600 n/a n/a n/a 10. Sheet Metal Worker GLSMW10 $57,400 $74,653 30.1% $74,340 11. Automotive / Heavy Duty Equipment Mechanic GLVHE10 $65,800 n/a n/a n/a 12. Carpenter GLWOW09 $62,800 $68,497 9.1% $64,030 13. Cleaner / Janitor GSBUS02 $40,700 $44,454 9.2% $42,283 14. Food Service Helper GSFOS02 $35,400 $40,864 15.4% $42,283 15. Cook GSFOS06 $42,500 $55,223 29.9% $59,794 16. Storesperson GSSTS04 $47,900 $55,703 16.3% $51,967 17. Stationary Engineer (2nd Class) HP04 $69,600 $61,756 -11.3% $73,443 2019 Ships’ Crew study

Missing from the 2015 Joint Hay Study results was the Ships’ Crews (SC) group as there was not enough participation to allow for meaningful results. Nonetheless, this group settled with a 5% wage adjustment along with the pattern established for economic increases. In addition, an MOU was included in the agreement to establish a joint committee with the union and the Employer to examine their compensation (Annex L).

In order to fulfill Annex L of the collective agreement, the PSAC and the Employer proceeded with a joint wage study for the SC group. This primary research study was completed by Mercer Canada in March of 2019 and was vetted by both the union and the Employer. The wage study consisted of four different SC jobs and the results showed that the SC positions surveyed all had wages which were comparable with the market (Table 17).

Table 17: SC wage study results

Compensation data in $Actual base salary Stream TBS position Classification level TBS maximum salary P50 ($) TBS maximum vs. market P50 Ships Crews Deckhand SC-02 $54,072 $54,140 0% Boatswain SC-05 $59,496 $56,420 5% Engine Room Assistant SC-03 $55,824 $55,968 0% Steward STD-01 $52,896 $50,450 5% Comments on the use of wage studies

Survey-based wage studies are one of many tools the Employer uses to determine fair salaries for their employees. They provide useful information in benchmarking occupation-specific salaries to external comparators. Nevertheless, their methodological limitations need to be taken into account; accordingly, they also need to be used in conjunction with other indicators of market comparability, such as recruitment and retention data and broader data on wage trends and economic conditions.

As is indicated by the comparison of the 2019 Mercer study and the 2015 Hay study, there can be significant variability in the results for individual occupational subgroups, due to the small sample sizes used in the studies, and other methodological limitations (e.g., inexact job matching). Accordingly, only results where there is a market gap greater than plus or minus 10% should be regarded as evidence of a misalignment with external comparators. Doing so otherwise imposes too high a level of precision on an imprecise tool, and risks adjusting wages for statistical artifacts rather than underlying wage trends. The use of plus or minus 10% is a generally accepted industry threshold among firms undertaking a wage comparison study.

In general, salary adjustments should only be provided where there is clear evidence of a sustained misalignment of salaries with comparators. There is no practical means of adjusting salaries downward in the future, if subsequent studies determine that federal government salaries for a particular occupation are significantly ahead of their comparators.

Group-specific wage adjustments also need to take account of internal relativity considerations. The government needs to ensure equal pay for equal value work, in order to respect its human rights obligations and to ensure a consistent approach in managing a diverse workforce. The government’s objective is to ensure overall alignment of wage rates with external comparators. However, it may not be possible to align wages with external comparators for some specific subgroups, where pay rates are not supported by internal relativity comparisons of value of work.

Finally, the studies completed also use the 50th percentile (P50) of the market as the relevant comparator to the TBS maximum salary range. The maximum level of a salary range is a good indicator of the expected salary of federal government employees. Generally, federal public sector base pay practices are calibrated such that employees will achieve the maximum base salary rate of pay (job rate) of their salary band based on a combination of tenure and performance. Currently approximately 70% of employees in the CPA are situated at the maximum salary in their pay range. External to the public sector at any given level, the 50th percentile of a defined labour market, typically represents the expected salary for “fully competent” job performance.

Progression beyond the 50th percentile midpoint is generally reserved for a high relative performance and advanced competency growth. The choice of the 50th percentile as an acceptable benchmark is consistent with TBS’s key guiding compensation principle; TBS wants compensation in the public service to be competitive with, but not lead, relevant external labour markets that provide similar work. Mercer also prefers P50 as it represents the middle of the market as the average could be skewed due to outliers.

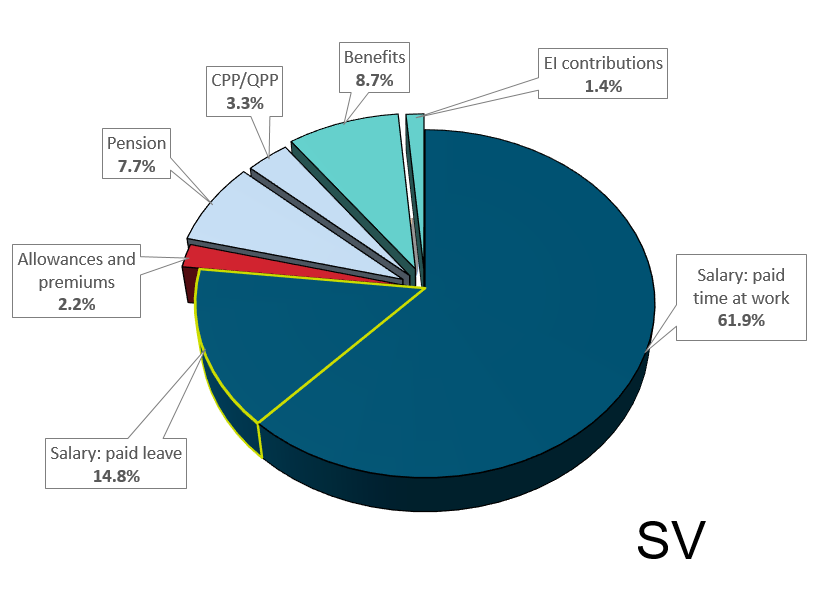

Total compensation comparability study

In 2014, Mercer was commissioned to develop a methodology to provide a value for pensions and benefits model for the federal government employees and external labour markets. This information can be combined with a base wage comparability study to estimate pensions and benefits and thereby total compensation. The Mercer report was updated in August 2019 to reflect changes in both the federal public service and the external market.

Mercer has a proprietary database containing detailed information on provisions, costs and eligibility for pensions and supplementary benefits, on an industry-by-industry basis. Using the Mercer study, Statistics Canada data and data from TBS incumbent system, TBS is able to compare pensions and benefits available for a specific public service position to that of an external market comparator, based on the industry in which the comparator works.

Included in Table 18 below are the results of this analysis. The results for the Construction Labourer (GL-ELE-03), Building Systems Maintenance Technician (GL-MAM-08), Food Service Helper (GS-FOS-02), Cook (GS-FOS-06), Shift Engineer (Non-supervisory) (HP-04) and Steward (SC-SCT-01) were found to be leading the market, while all of the remaining positions were deemed to be comparable with the market, with no position lagging.

It should also be noted that the results in the study compares TBS 2017 rates vs. 2018 markets rates, and that applying the Employer’s first year proposal would further improve its relativity with the market results.

Table 18: Total compensation study results

Summary table – by stream

Compensation data in $

This table below provide competitive positioning for TBS’ base salary compensation levels relative to the market median (P50) for all benchmark positions by stream.Stream Job TBS position Classification level TBS total compensation Base salary TBS vs. market total compensation variance 3 TBS maximum salary 1 Estimated pensions and benefits 4 Total compensation Average market P50 salary 2 Estimated pensions and benefits 4 Total compensation ($) (%) - Reflects the maximum base salary range effective as of June 21, 2017, provided by TBS.

- Reflects the average of all benchmark jobs in the classification. Market data presented for all survey sources is on an organization-weighted basis.

- Represents the market variance between TBS's total compensation to the external market total compensation calculated using the following formula: (TBS total compensation – Market total compensation) / Market total compensation.

- Estimates based on a calculator developed by Mercer designed to estimate the value of pensions and benefits for TBS and the market results for a given job. The following elements are included in the pensions and benefits estimate: pensions, medical, dental, HCSA, STD, LTD, life insurance, retiree medical, retiree dental, retiree HCSA, and retiree life insurance. Other than STD and LTD, estimates provided do not control for other forms of paid leave. Due to data limitations, maternity and parental top-ups, personal leave, family-related leave, and Retirement Compensation Arrangement for senior levels are not included in these estimates.

Legend:

- > Above Comparator Market (Greater than +10%)

- ± Within Comparator Market (± 10%)

- < Below Comparator Market (Less than -10%)

Comparison of external wage growth

As is shown in Table 19, the wage growth for the majority of the SV groups (40.5% to 93.9%) has significantly outpaced increases in the public sector (43.3%, as measured by HRSDC Footnote 6 ), private sector (43.6%, as measured by HRSDC Footnote 6 ), and cumulative increases as represented by the change in CPI inflation (36.8%) since 2000. This is despite the negative impact of the Expenditure Restraint Act in 2010-2011 and the Deficit Reduction Action Plan from 2011–12 to 2015–16.

Table 19: SV wage growth vs. other sectors between 2000 and 2017

External cumulative increase comparison (2000 –2017)

HRSDC public sector HRSDC private sector CPI SV group FR GL GS HP HS LI SC PR(S) Cumulative increase 43.3% 43.6% 36.8% 81.8% 66.7% 59.4% 93.9% 56.1% 55.0% 54.0% 40.5% Notes: SV rates calculated by TBS from settlement rates (weighted average). 2.3 Internal relativity

As stated in the FPSLRA, there is a need to maintain appropriate relationships with respect to compensation between classifications and levels. Moreover, as noted in the Policy Framework on the Management of Compensation, compensation should reflect the relative value to the Employer of the work performed, so ranking of occupational groups relative to one another is a useful indicator of whether their relative value and relative compensation align. Exhibit #9 shows a ranking of average salaries for occupational groups in the CPA as of March 31, 2018, and how the PSAC’s proposed increases for the FR and HP groups would disrupt internal relativity between classifications.

Table 20 shows the cumulative increases for the SV subgroups and the overall CPA average. As shown in the table, the cumulative increases received by the majority of the SV employees are significantly above the CPA average, more than double in the case of the HP group.

Table 20: SV wage growth vs. CPA Footnote 7

Internal cumulative increase comparison (2000–2017)CPA average SV group FR GL GS HP HS LI SC PR(S) Cumulative increase 45.5% 81.8% 66.7% 59.4% 93.9% 56.1% 55.0% 54.0% 40.5% Notes: SV and CPA rates calculated by TBS from settlement rates (weighted average). 2.4 The state of the economy and the government’s fiscal situation

The state of the economy and the government’s fiscal circumstances are critical considerations for the federal government in its role as Employer.

The new collective agreement for the SV group will cover a time frame of low to moderate economic growth. Moreover, there are negative risks associated with the economic outlook, which could lead to weaker labour markets and lower wage growth than what is now broadly expected. With interest rates at near-record lows in major advanced economies and signs of a deteriorating global outlook, a focus on keeping federal government compensation affordable relative to the country’s economic performance will allow the government to pursue its budgetary commitments and better respond to future economic uncertainty.

The following sections outline Canadian economy and its outlook, labour market conditions for the public service relative to the private sector, and the government’s fiscal circumstances. This includes an overview of gross domestic product (GDP) growth, consumer price inflation, employment growth, risks to the economic outlook, and how the public service compares against the typical Canadian worker, which is the ultimate payer of public services.

Real GDP growth

Real GDP growth, which is the standard measure of economic growth in Canada, provides an indication of the overall demand for goods, services, and labour. Lower real GDP growth reduces demand for employment, which increases unemployment and curbs wage increases.

Real GDP growth recently peaked in 2017 at 3.2% before slowing markedly to 2.0% in 2018 (Table 21). The outlook for real GDP projects growth further deteriorating to 1.7% in 2019 and in 2020. Over the 2014 to 2017 period, real economic growth averaged 2.1%, higher than the average outlook for growth of 1.8% over the 2019 to 2021 period. The slowing growth profile of GDP comes despite the economy’s continued reliance on historically low interest rates.

Table 21: Real gross domestic production, year-over-year growth

Real GDP growth (year to year) 2016 2017 2018 2019 (forecast) 2020 (forecast) 2021 (forecast) Statistics Canada 1.1% 3.2% 2.0% n/a n/a n/a Consensus Forecasts n/a n/a n/a 1.7% 1.7% 1.9% Bank of Canada n/a n/a n/a 1.5% 1.7% n/a Source: Statistics Canada, Consensus Forecasts, December 2019, Bank of Canada, Monetary Policy Report October 2019.

While forecasters are basing their modest expectations for growth on the assumption that economic conditions will not further deteriorate, the Canadian economy faces a number of risks that could further compromise growth prospects, weakening the labour market and the government’s fiscal balance.

The Consumer Price Index

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) tracks the price of a typical basket of consumer goods. Measuring price increases against wage growth demonstrates relative purchasing power over time.

Recent inflation has been persistently low, below the 2.0%mid-point of the Bank of Canada’s 1.0 to 3.0% target rate since 2011. Inflation exceeded 2.0% for the first time in seven years in 2018, at 2.3%. However, inflation above 2.0% is forecast to be short-lived. According to Consensus Forecasts, inflation is expected to decline to 2.0% in 2019 and further decline to 1.9% in 2020 and 2021 (Table 22). The Bank of Canada’s October inflation forecast has a similarly low profile, with inflation at or below 2.0% until the end of 2021.

Table 22: Canada’s major economic indicators, year-over-year growth

Indicator Footnote 8 2016 2017 2018 2019 (forecast) 2020 (forecast) 2021 (forecast) CPI (year to year) Consensus 1.4% 1.6% 2.3% 2.0% 1.9% 1.9% CPI (year to year) Bank of Canada 1.4% 1.6% 2.3% 2.0% 1.8% 2.0% Unemployment 7.0% 6.3% 5.8% 5.7% 5.7% n/a Source: Statistics Canada, Consensus Forecasts (April 2021 long-term forecast and December 2019 for 2019, 2020, 2021 forecast), BoC MPR October 2019. Canadian employment growth

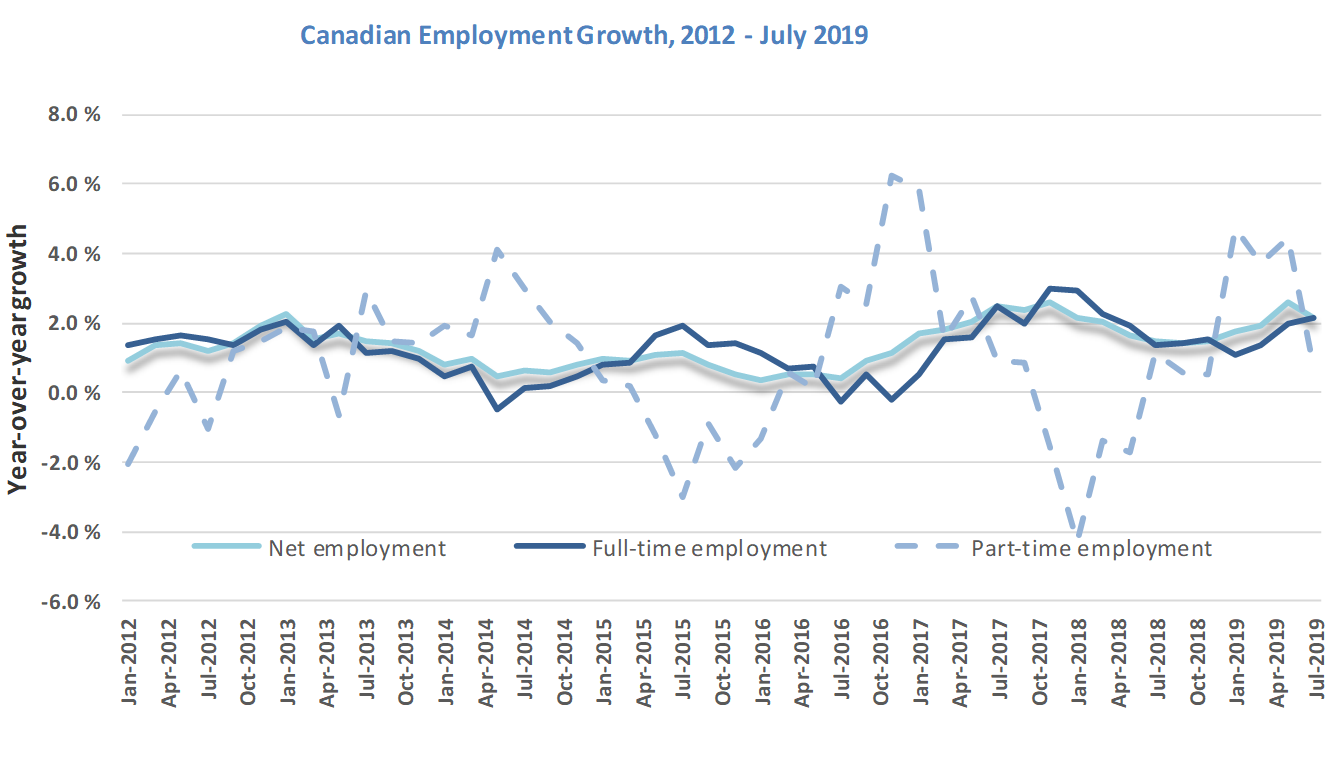

Canadian labour market conditions have improved with the unemployment rate declining from a high of 6.8% in January 2017 to a 40-year low of 5.4% in May 2019 Footnote 9 before recently jumping to 5.9% in November 2019. Footnote 10 A falling unemployment rate is unsurprising given that the net employment growth rate, which had lingered below 1.0% from November 2013 to March 2015, exceeded 2.0% in the summer and fall of 2017, and again in the summer of 2019 (Chart 1). Footnote 11

However, this labour market strength recently faded. “Canada’s labour market in November recorded its worst month for job losses in more than a decade,” Footnote 12 with employment declining almost 71,000, and the unemployment rate jumping 0.4 percentage points from 5.5% to 5.9% in the December 2019 release of Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey.

The unemployment rate had been forecasted to remain flat at 5.7% for 2019 and 2020 Footnote 13 (Table 22), but it should be noted that these forecasts were made before the most recent release of the large and unexpected 71,000 in job losses, and it will take some time for forecasters to update their expectations.

Up until November’s job losses and the sharp jump in the unemployment rate, it was surprising to many analysts that wage growth has fallen well short of expectations for a labour market with little unemployment and strong employment growth.

In Great Britain, weaker than expected wage growth in a strong labour market has been attributed to the new and quickly expanding informal or “gig” economy. According to the Bank of England’s chief economist, Footnote 14 “the rise of insecure work in the gig economy has fuelled a ‘lost decade’ in wage growth in Britain.”

A recent analytical paper examining the informal “gig” economy in Canada Footnote 15 uncovered similar evidence. The analysis found that just under one-third of Canadian survey respondents participate in gig work, especially younger workers, and that participation was often consistent with labour market slack.

Over a third of survey respondents who take part in informal work do so as a result of weak economic conditions, and over half would switch their hours worked for hours in formal employment with no increase in pay.

The “employment” Footnote 16 conditions of gig workers, with temporary and irregular hours, no job security or opportunity for advancement, with little or no paid sick leave and other benefits, contrasts sharply with the stable and secure employment with generous pensions and benefits in the federal public service.

These advantageous working conditions, examined further in the following section, have continued to attract large pools of qualified applicants for every job opportunity.

Working conditions in the public sector versus the private and other sectors

The public sector enjoys many privileges over what the average private sector worker experiences, with significant advantages in pension and benefit plan coverage and quality, better job tenure and stability, more paid time off and an earlier average age of retirement.